LSL Webinar “Back to Basics | Capital Assets Crash Course” presented Noah Daniels, CPA, CPFO, and James Butera, MBA, CPA, broke down the lifecycle of capital assets for local government finance departments.

In case you missed it – being audit-ready is essential for maintaining transparency, ensuring compliance with accounting standards, and fostering public trust. Capital assets, which often represent a significant portion of a municipality’s balance sheet, play a critical role in this process.

No matter if you’re new to this or simply need a quick reminder, you’re welcome to bookmark this post, save the link, or print out the examples for convenient reference in the future.

Reminder: What is a Capital Asset?

Capital assets are long-term assets used in operations, with a useful life extending beyond one year.

- Buildings: Administrative offices, libraries, public works facilities, etc.

- Infrastructure: Roads, bridges, water systems, etc.

- Land: Parks, vacant lots, and other government-owned land.

- Equipment: Vehicles, machinery, computers, etc.

- Intangible assets: Software, patents, and other non-physical assets.

Capitalization Audit Considerations

When capitalizing assets, there are several critical audit factors to consider. These can impact the accuracy and compliance of financial reporting:

- Disposal Process: When capitalizing asset groups, ensure disposals are able to be tracked if disposed of individually.

- Ineligible Expenditures: Avoid capitalizing expenses that do not qualify as capital assets, such as repairs and maintenance or feasibility studies.

- Capital Outlay: Compare total capital outlay per the governmental fund General Ledger (GL) to total asset additions before an audit to ensure no material omissions. Ensure that repairs and maintenance accounts are reviewed for misclassified items.

- Timing of Additions: Assets not received by June 30 should not be recorded as additions in the financial statements.

- Policy Updates: Ensure your capitalization policies are updated to include thresholds for GASB 87 (leases) and GASB 96 (Subscription-Based Information Technology Arrangements or SBITAs). Be mindful of correctly applying thresholds to avoid misstatements.

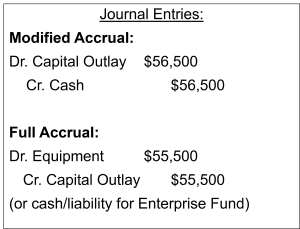

Example: Purchase of Equipment

The Public Works Department purchases new equipment for street maintenance:

- Purchase Cost: $50,000

- Delivery and Handling: $1,500

- Installation (toolbox and safety lights): $3,500

- Registration and Licensing: $500

- Initial Training: $1,000

The total historical cost of the equipment is $55,500, as training costs are not capitalized as part of the asset’s value.

The historical cost method records an asset’s purchase price plus any eligible costs necessary to prepare it for use.

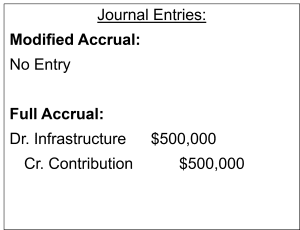

Example: Donated Infrastructure

A developer donates infrastructure (valued at $500,000) to the City as part of a new subdivision project. This infrastructure includes roads, sidewalks, and storm drains.

Capital Asset Additions – The Audit Process

Auditors often review capital asset additions separately based on whether the assets are depreciable or non-depreciable. To ensure a smooth audit, consider the following:

- Supporting Documentation: Compile checks, invoices, and receiving documentation in a network drive throughout the year to ease the burden of retrieving support during fieldwork.

- Enterprise Fund CIP: Ensure that expense listings of capitalized Construction Work In Progress (CIP) projects are ready for auditors.

Depreciation – Audit Notes

Depreciation is another key focus for auditors:

- Recalculation and Assessment: Auditors may perform various tests on depreciation, including recalculations and assessments of useful life reasonableness.

- Fully Depreciated Assets: Review and have records of fully depreciated assets as of the year-end date.

- Useful Life Reviews: Ensure that asset useful lives align with policy and are reasonable based on category of asset.

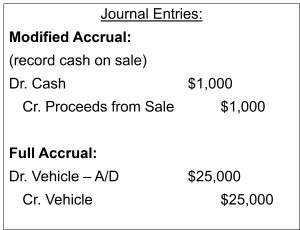

Disposal Process – Audit Notes

Disposals can complicate capital asset management. Here are some tips for ensuring accurate reporting:

- Approval Documentation: Retain notice of completion approvals for transferring CIP assets into depreciable categories, such as infrastructure.

- Surplus Equipment: Keep records of approvals for surplus equipment designations, auction sale documentation, and gain/loss support for sold assets.

CIP Rollforward

A good practice for both Cities with large volumes of CIP projects and smaller agencies is to generate rollforwards to track project status:

- Rollforward: Should show beginning balances by project, “additions” (current year project expenditures), “deletions” (total cost of project upon completion to zero out the balance), and ending balance.

- Outdated Projects: Assists to ensure outdated projects are not included in the ending CIP balance.

- Project Completion Approvals: Maintain records of completion approvals or references to Council/Board meetings where the approvals were granted.

Conclusion

Managing capital assets is a crucial aspect of local government finance, impacting financial statements, operational efficiency, and audit readiness. Whether it’s acquiring new equipment, handling infrastructure donations, or managing depreciation and disposals, having a clear process in place not only streamlines financial reporting but also reduces the risk of errors during audits.

For more comprehensive guidance on how to manage capital assets – check out the blog ‘Capital Assets Crash Course: Handbook for Local Government Finance’.